Collaborating with git repositories

Last updated on 2024-07-31 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I contribute to a shared repository?

- How can I contribute to a public repository without write access?

Objectives

- Understand how to share a repository collaboratively.

- Learn how to contribute a pull request.

Collaborating with git remotes

One of the major advantages of version control systems is the ability to collaborate, without having to email each other files, or bother about sharedrives. We’ll consider two scenarios for collaboration:

- A remote repository where collaborators each have write acess

- A remote repository where you do not have write access

A remote with write access

Remember that a git remote is simply a copy of the .git

directory. It contains the instructions for how to recreate any state in

the history that has been captured. If more than one person is

contributing to a collaborative remote, there will be a shared history.

That is, the copy on the remote will be a combination of the history

between the collaborators.

Discussion

What do you think will happen if two collaborators make their own

sequence of commits on main and try to push them to the

same remote?

To make sure that you don’t end up with a mess of conflicting commits, it’s essential to have an agreed strategy for how to manage your contributions.

There are different models that can work, and depending on the complexity of each situation might be appropriate.

There’s a good discussion of different models, including git-flow here.

To be absolutely sure your local work won’t conflict with someone

else’s, always work on your own branch. Don’t commit directly to

main, but only merge your branch onto main

after discussion with your collaborators, or through a pull request

(discussed below).

A remote without write access

Lots of open source projects welcome contributions from the community, but clearly don’t want to give write access to just anyone. Instead, a very commonly used approach is to accept pull requests from forked versions of the repository.

Forking a repo

Forking a repository is making your own copy of a remote. For

example, a Data School example repo is hosted at

bitbucket.csiro.au/scm/dat/programmatic-data-example. By

forking that repository, you can have your own copy, retaining the

complete history of the project, at

bitbucket.csiro.au/scm/<your_username>/programmatic-data-example.

To fork a repository on Bitbucket, click on the Create Fork button in the lefthand menu of a repository’s page.

Submitting a pull request

To contribute a change to a repository that you don’t have write access to, you first of all need to make your own copy (fork the repo) which you do have write access to. You can then make your changes to the repo, and push them to your own fork.

To get them into the original repo (if that’s what you want), you need to ask the maintainers of that repository to accept them, through a pull request. You are requesting that the repository “pull” in your changes.

Pull requests as a collaborative framework

Pull requests can also be useful on a repository that you do

have write permissions on, as a collaborative, organisational, and

record-keeping tool. A common working pattern, when using Git in a team,

is to complete a body of work on a separate branch and then, rather than

doing a git merge, instead create a pull request. In doing

so, you can: * Invite collaborators to review your changes * Create

discussion around the changes (with discussions saved for posterity) *

Continue to make further edits to your changes before finally merging *

Save a formalised record of these steps having taken place

An open pull request may continue to receive further commits, by pushing changes to the same branch. This allows a pull request to act as a draft step, under review, until finally approved to ‘merge’.

Pull requests on Bitbucket

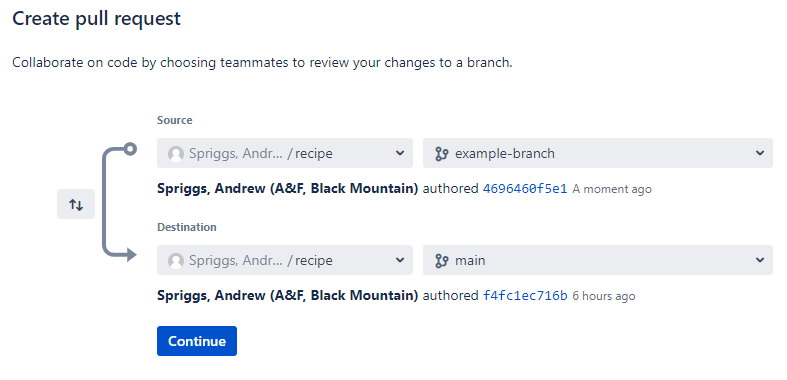

The option to create a Pull request on Bitbucket may be found in the lefthand menu of a repository’s page.

You’ll then be asked to select a source branch (the branch with new

work) and a target or destination branch (the branch to

merge into).

Next you’ll be able to write a description of what the pull request is about, and request specific teammates as “reviewers” of the request, before confirming the pull request.

With the pull request open, options include looking at the commits and file changes involved, writing discussion comments, starting an official review, making edits, etc.. The final goal would usually be the ‘Merge’ button, to the top-right, however other outcomes may be to decline or delete the pull request.

Challenge

Form teams of 2-3 people. One person will start.

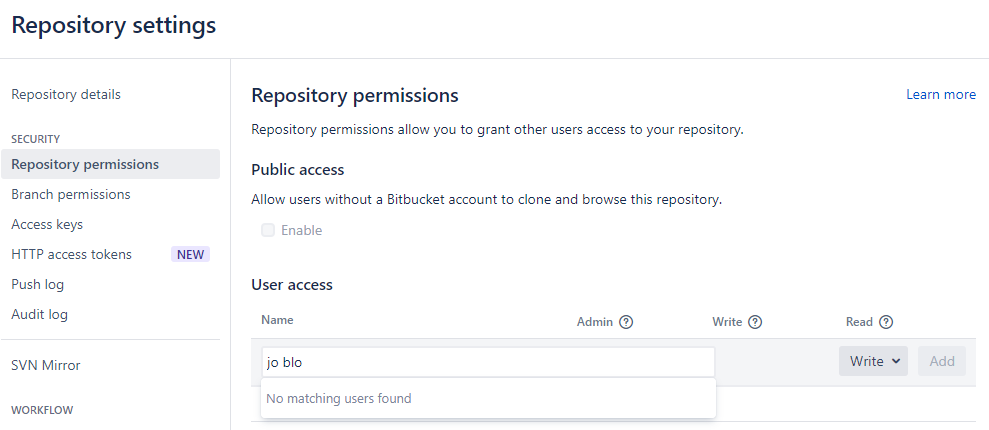

Person 1: 1. One person from each team should create a new Bitbucket

repository named ‘favourite-things’. 2. Copy the supplied

git clone command to create a local copy. 3. Locally,

create a file named README.md and list a few of your

favourite things within it. 4. Use git add,

git commit and git push to move your new file

back to the remote. 5. In the Bitbucket repository, click ‘Repository

Settings’ in the lefthand menu, followed by ‘Repository permissions’.

Use the form to give “User access” with “Write” permissions to your team

member(s).

6. Share the repository link to your team member(s).

After the above, other team member(s) then: 1. Use

git clone to create a local copy of the ‘favourite-things’

repository. 2. Create and switch to a new branch (with a

meaningful name). 3. Edit the README.md file to add a few

of your own favourite things to it. 4. Use git add,

git commit and git push to get your changes to

the remote (still on your new branch). 5. On Bitbucket create a Pull

Request that would merge your new branch into the original.

Finally, together, explore the created Pull Request(s) on Bitbucket and finally “merge” them.

Bonus discussion: Why was the suggested filename ‘README.md’ specifically?

Key Points

- Sharing a repository needs good communication.

- Branches are really necessary.

- Pull requests enable sensible merging of changes between branches and across repositories.