Branching and merging

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How can I or my team work on multiple features in parallel?

How to combine the changes of parallel tracks of work?

How can I permanently reference a point in history, like a software version?

Objectives

Be able to create and merge branches.

Know the difference between a branch and a tag.

Motivation for branches

In the previous section we tracked a guacamole recipe with Git.

Up until now our repository had only one branch with one commit coming after the other:

- Commits are depicted here as little boxes with abbreviated hashes.

- Here the branch

mainpoints to a commit. - “HEAD” is the current position (remember the recording head of tape recorders?).

- When we talk about branches, we often mean all parent commits, not only the commit pointed to.

Now we want to do this:

Software development is often not linear:

- We typically need at least one version of the code to “work” (to compile, to give expected results, …).

- At the same time we work on new features, often several features concurrently. Often they are unfinished.

- We need to be able to separate different lines of work really well.

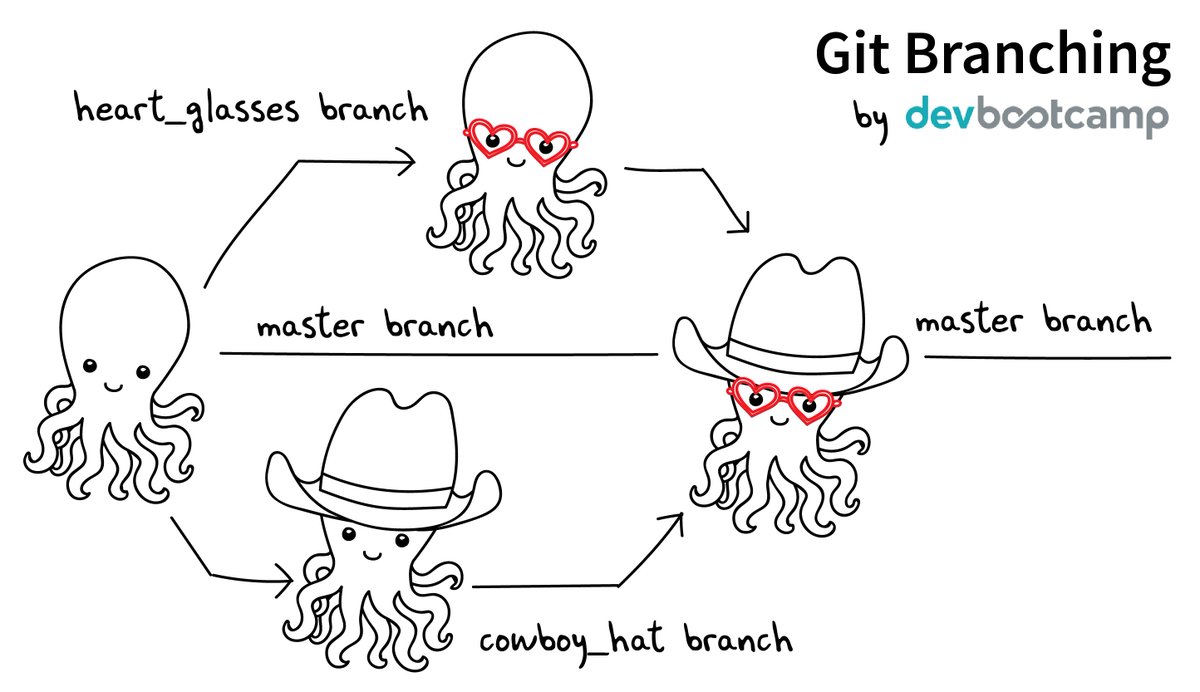

The strength of version control is that it permits the researcher to isolate different tracks of work, which can later be merged to create a composite version that contains all changes:

- We see branching points and merging points.

- Main line development is often called

main(ormasterin older conventions). - Other than this convention there is nothing special about

main, it is just a branch. - Commits form a directed acyclic graph (we have left out the arrows to avoid confusion about the time arrow).

A group of commits that create a single narrative are called a branch. There are different branching strategies, but it is useful to think that a branch tells the story of a feature, e.g. “fast sequence extraction” or “Python interface” or “fixing bug in matrix inversion algorithm”.

A useful alias

We will now define an alias in Git, to be able to nicely visualize branch structure in the terminal without having to remember a long Git command:

$ git config --global alias.graph "log --all --graph --decorate --oneline"

Let us inspect the project history using the git graph alias:

$ git graph

* dd4472c (HEAD -> main) we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

- We have three commits and only

one development line (branch) and this branch is called

main. - Commits are states characterized by a 40-character hash (checksum).

git graphprint abbreviations of these checksums.- Branches are pointers that point to a commit.

- Branch

mainpoints to commitdd4472c8093b7bbcdaa15e3066da6ca77fcabadd. HEADis another pointer, it points to where we are right now (currentlymain)

On which branch are we?

To see where we are (where HEAD points to) use git branch:

$ git branch

* main

- This command shows where we are, it does not create a branch.

- There is only

mainand we are onmain(star represents theHEAD).

In the following we will learn how to create branches, how to switch between them, how to merge branches, and how to remove them afterwards.

Creating and working with branches

Let’s create a branch called experiment where we add cilantro to ingredients.txt.

$ git branch experiment main # create branch called "experiment" from main

# pointing to the present commit

$ git switch experiment # switch to branch "experiment"

$ git branch # list all local branches and show on which branch we are

- Verify that you are on the

experimentbranch (note thatgit graphalso makes it clear what branch you are on:HEAD -> branchname):

$ git branch

* experiment

main

- Then add 2 tbsp cilantro on top of the

ingredients.txt:

* 2 tbsp cilantro

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

* 2 tsp salt

* 1/2 onion

- Stage this and commit it with the message “let us try with some cilantro”.

- Then reduce the amount of cilantro to 1 tbsp, stage and commit again with “maybe little bit less cilantro”.

We have created two new commits:

$ git graph

* 6feb49d (HEAD -> experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

* 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

* dd4472c (main) we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

- The branch

experimentis two commits ahead ofmain. - We commit our changes to this branch.

Interlude: The multipurpose “checkout” command

Older versions of git used

git checkoutfor the actions now handled by bothrestoreandswitch.git checkoutcan still be found in a lot of documentation, Git tools, and scripts. Depending on the contextgit checkoutcan do very different actions:1) Switch to a branch:

$ git checkout <branchname>2) Bring the working tree to a specific state (commit):

$ git checkout <hash>3) Set a file/path to a specific state (throws away all unstaged/uncommitted changes):

$ git checkout <path/file>This is unfortunate from the user’s point of view but the way Git is implemented it makes sense. Picture

git checkoutas an operation that brings the working tree to a specific state. The state can be a commit or a branch (pointing to a commit).In Git 2.23 (2019-08-16) and later this is much nicer:

$ git switch <branchname> # switch to a different branch $ git restore <path/file> # discard changes in working directory

Exercise: create and commit to branches

In this exercise, you will create two new branches, make new commits to each branch. We will use this in the next section, to practice merging.

- Change to the branch

main.- Create another branch called

less-salt

- Note! makes sure you are on main branch when you create the less-salt branch

- A safer way would be to explicitly mention to create from the main branch as shown below

git branch less-salt main- where you reduce the amount of salt.

- Commit your changes to the

less-saltbranch.Use the same commands as we used above.

We now have three branches (in this case

HEADpoints toless-salt):$ git branch experiment * less-salt main $ git graph * bf59be6 (HEAD -> less-salt) reduce amount of salt | * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro | * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro |/ * dd4472c (main) we should not forget to enjoy * 2bb9bb4 add half an onion * 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructionsHere is a graphical representation of what we have created:

- Now switch to

main.- Add and commit the following

README.mdtomain:# Guacamole recipe Used in teaching Git.Now you should have this situation:

$ git graph * 40fbb90 (HEAD -> main) draft a readme | * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt |/ | * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro | * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro |/ * dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy * 2bb9bb4 add half an onion * 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

And for comparison this is how it looks on GitHub.

Merging branches

It turned out that our experiment with cilantro was a good idea.

Our goal now is to merge experiment into main.

First we make sure we are on the branch we wish to merge into:

$ git branch

experiment

less-salt

* main

Then we merge experiment into main:

$ git merge experiment

We can verify the result in the terminal:

$ git graph

* c43b24c (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'experiment'

|\

| * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

| * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

* | 40fbb90 draft a readme

|/

| * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

What happens internally when you merge two branches is that Git creates a new commit, attempts to incorporate changes from both branches and records the state of all files in the new commit. While a regular commit has one parent, a merge commit has two (or more) parents.

To view the branches that are merged into the current branch we can use the command:

$ git branch --merged

experiment

* main

We are also happy with the work on the less-salt branch. Let us merge that

one, too, into main:

$ git branch # make sure you are on main

$ git merge less-salt

We can verify the result in the terminal:

$ git graph

* 4f00317 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'less-salt'

|\

| * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt

* | c43b24c Merge branch 'experiment'

|\ \

| * | 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

| * | 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

| |/

* | 40fbb90 draft a readme

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

Observe how Git nicely merged the changed amount of salt and the new ingredient in the same file without us merging it manually:

$ cat ingredients.txt

* 1 tbsp cilantro

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

* 1 tsp salt

* 1/2 onion

If the same file is changed in both branches, Git attempts to incorporate both changes into the merged file. If the changes overlap then the user has to manually settle merge conflicts (we will do that later).

Deleting branches safely

Both feature branches are merged:

$ git branch --merged

experiment

less-salt

* main

This means we can delete the branches:

$ git branch -d experiment less-salt

Deleted branch experiment (was 6feb49d).

Deleted branch less-salt (was bf59be6).

This is the result:

Compare in the terminal:

$ git graph

* 4f00317 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'less-salt'

|\

| * bf59be6 reduce amount of salt

* | c43b24c Merge branch 'experiment'

|\ \

| * | 6feb49d maybe little bit less cilantro

| * | 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

| |/

* | 40fbb90 draft a readme

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

As you see only the pointers disappeared, not the commits.

Git will not let you delete a branch which has not been reintegrated unless you

insist using git branch -D. Even then your commits will not be lost but you

may have a hard time finding them as there is no branch pointing to them.

Exercise: encounter a fast-forward merge

- Create a new branch from

mainand switch to it.Create a couple of commits on the new branch (for instance edit

README.md):

- Now switch to

main.- Merge the new branch to

main.- Examine the result with

git graph.- Have you expected the result? Discuss what you see.

The following exercises are advanced, absolutely no problem to postpone them to a few months later. If you give them a go, keep in mind that you might run into conflicts, which we will learn to resolve in the next section.

(Optional) Exercise: Moving commits to another branch

Sometimes it happens that we commit to the wrong branch, e.g. to

maininstead of a feature branch. This can easily be fixed:

- Make a couple of commits to

main, then realize these should have been on a new feature branch.- Create a new branch from

main, and rewindmainback usinggit reset --hard <hash>.- Inspect the situation with

git graph. Problem solved!

(Optional) Exercise: Rebasing

As an alternative to merging branches, one can also rebase branches. Rebasing means that the new commits are replayed on top of another branch (instead of creating an explicit merge commit). Note that rebasing changes history and should not be done on public commits!

- Create a new branch, and make a couple of commits on it.

- Switch back to

main, and make a couple of commits on it.- Inspect the situation with

git graph.- Now rebase the new branch on top of

mainby first switching to the new branch, and thengit rebase main.- Inspect again the situation with

git graph. Notice that the commit hashes have changed - think about why!

(Optional) Exercise: Squashing commits

Sometimes you may want to squash incomplete commits, particularly before merging or rebasing with another branch (typically

main) to get a cleaner history. Note that squashing changes history and should not be done on public commits!

- Create two small but related commits on a new feature branch, and inspect with

git graph.- Do a soft reset with

git reset --soft HEAD~2. This rewinds the current branch by two commits, but keeps all changes and stages them.- Inspect the situation with

git graph,git statusandgit diff --staged.- Commit again with a commit message describing the changes.

- What do you think happens if you instead do

git reset --soft <hash>?

Summary

Let us pause for a moment and recapitulate what we have just learned:

$ git branch # see where we are

$ git branch <name> # create branch <name>

$ git switch <name> # switch to branch <name>

$ git merge <name> # merge branch <name> (to current branch)

$ git branch -d <name> # delete merged branch <name>

$ git branch -D <name> # delete unmerged branch <name>

Since the following command combo is so frequent:

$ git branch <name> # create branch <name>

$ git switch <name> # switch to branch <name>

There is a shortcut for it:

$ git switch -c <name> # Create branch <name> and switch to it

Typical workflows

With this there are two typical workflows:

$ git switch -c new-feature # create branch, switch to it

$ git commit # work, work, work, ...

# test

# feature is ready

$ git switch main # switch to main

$ git merge new-feature # merge work to main

$ git branch -d new-feature # remove branch

Sometimes you have a wild idea which does not work. Or you want some throw-away branch for debugging:

$ git switch -c wild-idea

# work, work, work, ...

# realize it was a bad idea

$ git switch main

$ git branch -D wild-idea # it is gone, off to a new idea

# -D because we never merged back

No problem: we worked on a branch, branch is deleted, main is clean.

(Optional) Tags

- A tag is a pointer to a commit but in contrast to a branch it does not move.

- We use tags to record particular states or milestones of a project at a given point in time, like for instance versions (have a look at semantic versioning, v1.0.3 is easier to understand and remember than 64441c1934def7d91ff0b66af0795749d5f1954a).

- There are two basic types of tags: annotated and lightweight.

- Use annotated tags since they contain the author and can be cryptographically signed using GPG, timestamped, and a message attached.

Let’s add an annotated tag to our current state of the guacamole recipe:

$ git tag -a nobel-2020 -m "recipe I made for the 2020 Nobel banquet"As you may have found out already,

git showis a very versatile command. Try this:$ git show nobel-2020For more information about tags see for example the Pro Git book chapter on the subject.

Test your understanding

- Which of the following combos (one or more) creates a new branch and makes a commit to it? 1.

$ git branch new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit2.

$ git add file.txt $ git branch new-branch $ git switch new-branch $ git commit3.

$ git switch -c new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit4.

$ git switch new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit- What is a detached

HEAD?- What are orphaned commits?

Solutions

- Both 2 and 3 would do the job. Note that in 2 we first stage the file, and then create the branch and commit to it. In 1 we create the branch but do not switch to it, while in 4 we don’t give the

-cflag togit switchto create the new branch.- When you check out a branch name, HEAD will point to the most recent commit of that branch. You can however check out a particular hash. This will bring your working directory back in time to that commit, and your HEAD will be pointing to that commit but it will not be attached to any branch. If you want to make commits in that state, you should instead create a new branch:

git switch -c test-branch <hash>.- An orphaned commit is a commit that does not belong to any branch, and therefore doesn’t have any parent commits. This could happen if you make a commit in a detached HEAD state. Commits rarely vanish in Git, and you could still find the orphaned commit using

git reflog.

Key Points

A branch is a division unit of work, to be merged with other units of work.

A tag is a pointer to a moment in the history of a project.